Welcome! While I set up this permanent personal website to house my research and data, please visit my Princeton University scholar site for my updated Research and Teaching pages. This page currently holds only the supplementary online material for my dissertation. If you’re interested in that, please read on. (Soon, everything will be hosted here.)

Dissertation

My dissertation analyzes competing criminal organizations and state security forces to explain subnational variation in homicidal violence trends in contemporary Mexico, ultimately seeking to explain when and how order and peace arises in violent criminal contexts. This project involved field trips to several northern Mexican cities, work with a small team of excellent research assistants based in Mexico, and the construction of new datasets to map the presence and strength of criminal groups and local security apparatuses at the state, metropolitan, and municipal level. Click on “Read More” for an abstract.

Dissertation: Online supporting materials

The project involved constructing or adapting several new data sources and carrying out a bit of supplementary work that did not make it into the dissertation itself. I’m making those data and research notes available here. Some of this work was produced with the help of excellent research assistants Marisol Torres (2019–2021), Diego Mendoza (2019–2021), and Mónica Torres (2019).

If you use any of these data or documents, I’d love to hear about it (patrick.signoret [at] outlook.com). We put a lot of time into it, so it’ll always be nice to hear when it supported others’ research. (Soy mexicano y hablo español, por cierto.)

Intentional lethal violence

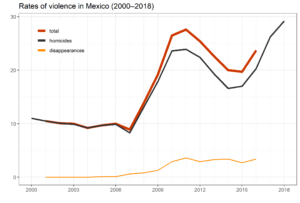

The most complete, trustworthy, and detailed data on homicides in Mexico is that gathered by the national statistics office, Inegi. However, a significant amount of lethal violence related to organized criminal groups (and, sometimes, government security forces), especially since 2008, has occurred in the form of forced disappearances; that is, killing people and hiding or destroying their bodies. In some states such as Tamaulipas, such violence represented an enormous share of the total (and likely still does), and relying on official homicides alone would have severely undercounted total violent deaths. I thus constructed “lethal violence” series that added homicides and a proxy for forced disappearances. I use a government database of missing persons, the “National Registry of Missing or Disappeared Persons” (Registro Nacional de Personas Extraviadas o Desaparecidas, RNPED). This data includes people reported missing or known to have been disappeared despite the lack of a body or other form of confirmation. With no death certificate or confirmed motive of death, these cases are not counted by Inegi. Of course, the database also includes voluntary missing persons (runaways) and disappearances unrelated to organized crime. Thus these numbers might overcount intentional homicides. On the other hand, the data probably does not include all cartel-related disappearances, since there may have been no one available or willing to make the report or those reporting may not have had knowledge of the whereabouts of the missing person, at least not down to the municipal level (which is the information I use). Patterns of disappearances coincide closely with known turf wars and in particular with known episodes in which a lot of people were disappeared, such as Durango City and several locations in Tamaulipas. I believe that including this data provides a good proxy for total intentional lethal violence and a much superior series to regular homicides.

I am updating my population, homicide, and disappearance series based on 2020 census data, and will post it all here shortly.

Criminal group presence: Monterrey and La Laguna

A major parallel project to my dissertation has been the collection of detailed data on organized criminal group presence, part of the Mapping Criminal Organizations project, which I co-founded with fantastic partners in multiple universities. Through that project we have made public maps and data on criminal group presence at the state and month level from 2007 to 2015, with other datasets forthcoming. For my dissertation specifically, with a team of research assistants I produced hand-coded municipal-level data for two core cities: the metropolitan areas of Monterrey, which had 12 municipalities in 2010, and La Laguna, which had four. This data collection was based on intensive archival work complemented by field research. There were three parallel tracks: background and follow-up research based on secondary sources, field research in both cities, and systematic online searches. My final coding of annual criminal group presence by municipality are based on a combination of the three, which complemented and fed into each other. Lucky readers of my dissertation appendices will get to learn the details (and I’ll post them here, too). For now, here’s the data.

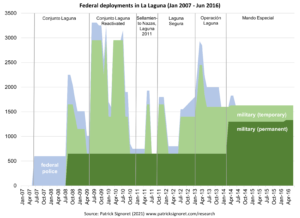

Federal deployments in La Laguna and Monterrey

My dissertation’s core case studies the onset and decline of criminal group conflict in Monterrey and La Laguna. In both, I considered the role of the state security apparatus, including deployed federal police and military personnel. That required numbers on the composition and size of deployments across time. Because systematic and detailed data was not available, I produced my own by combing newspaper archives, freedom of information requests, and other open sources. I went into particular detail for the case of La Laguna to understand how these deployments “worked”—who was deployed, for how much time, how frequently forces were rotated, and how lethal violence responded to these changes. Here is the data, Evernotes with information on the sources behind the data, and PDF versions of those Evernotes.

Monterrey federal deployments (sources)

La Laguna federal deployments (sources and data)

- Online appendix: Sources for Laguna federal deployments (Evernote). Or PDF version.

- La Laguna federal deployments data (Excel).

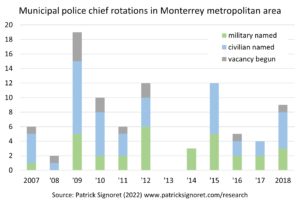

Police chiefs and prosecutors

Part of my work “mapping the security apparatus” involved collecting and analyzing information on the heads of public security and criminal justice institutions at the municipal and state level for parts of northern Mexico. At the municipal level, three research assistants and I gathered information on the heads of municipal public security for 11 Monterrey municipalities from January 2007 to October 2018, a period covering four mayoral terms. We documented 95 distinct episodes of public security leadership, 80 with a director at the helm and 15 in which the position was vacant for at least one month. Setting aside the departures of the last set of police chiefs (those in place as of October 2018), there were 71 departures of police chiefs across the metropolitan area. We collected similar data for La Laguna, and also for the state heads of public security (secretarios de seguridad pública or equivalent) and attorneys general (procuradores/fiscales generales de justicia). This dataset is mostly in Spanish.

- Police Chiefs and Prosecutors data (Excel file).

State and municipal police capacity in eight northern states

One chapter of my dissertation compares criminal dynamics, the security apparatus, and violence trajectories across eight northern states and their 21 largest cities. In that chapter, I compare the capacity of police forces in those states as estimated by their size and “quality”. Measuring police strength at the state level can be achieved along multiple dimensions: by the number of personnel involved in public safety, by the quality of institutions and personnel, or by total spending on public security and criminal justice. Moreover, we may focus on state institutions alone or also on the strength of all police bodies in a state, including municipal ones. Each measurement has advantages and disadvantages, and each varies in quality and availability. The main text of the dissertation collapses all measurements into a summary assessment for each state. The following document explains where I obtained the data and how I combined measurements.

Federal-state co-partisanship and violence

In a rich, comprehensive book on the politics behind criminal group conflict and behavior in Mexico (Votes, Drugs, and Violence, 2020), Guillermo Trejo and Sandra Ley trace the origins of inter-cartel wars to subnational political alternation in the late 20th and early 21st century, explain variation in the spikes of violence that occurred in parts of the country after 2007, and document and explain the expansion of criminal violence to local politics. I was particularly interested in the chapters in which they argued that federal interventions by the administration of Felipe Calderón (2006–2012) were shaped by partisan considerations. To sum it up in a sentence, they argue that federal interventions in states governed by the leftist PRD party, bitter political rivals of Calderón, were ineffective and harmful, whereas in other states, especially those with co-partisan (PAN) governors, federal interventions were cooperative and effective. Having studied spirals of violence in northern Mexico with particular interest in the federal government’s role, I was curious whether PAN-governed territories did, in fact, fare better than opposition-governed ones (despite no northern state being governed by the PRD at the time), so I reexamined some of the evidence in the book. In fact, I found partisanship to be a poor predictor of outcomes during and after the Calderón administration. The following research note explains.